The WPJ

THE WORLD PROPERTY JOURNALReal Estate Facts Not Fiction

Residential Real Estate News

Relaxed Zoning in U.S. Could Create Millions of New Homes

Residential News » Denver Edition | By Monsef Rachid | January 7, 2020 8:14 AM ET

According to Zillow research, allowing for even modest amounts of new density in the nation's overwhelmingly single-family neighborhoods across the U.S. could lead to millions of new homes nationwide, helping alleviate a housing affordability crisis that has been decades in the making.

If the Los Angeles area, for example, continues to add housing largely as it has over the past two decades it could grow its housing stock by an estimated 14.5% over the next two decades. But if 1 in 10 single-family lots were redeveloped or otherwise allowed to accommodate a second home, the area's housing stock could grow by 21% over the same period - or nearly 387,000 additional homes.

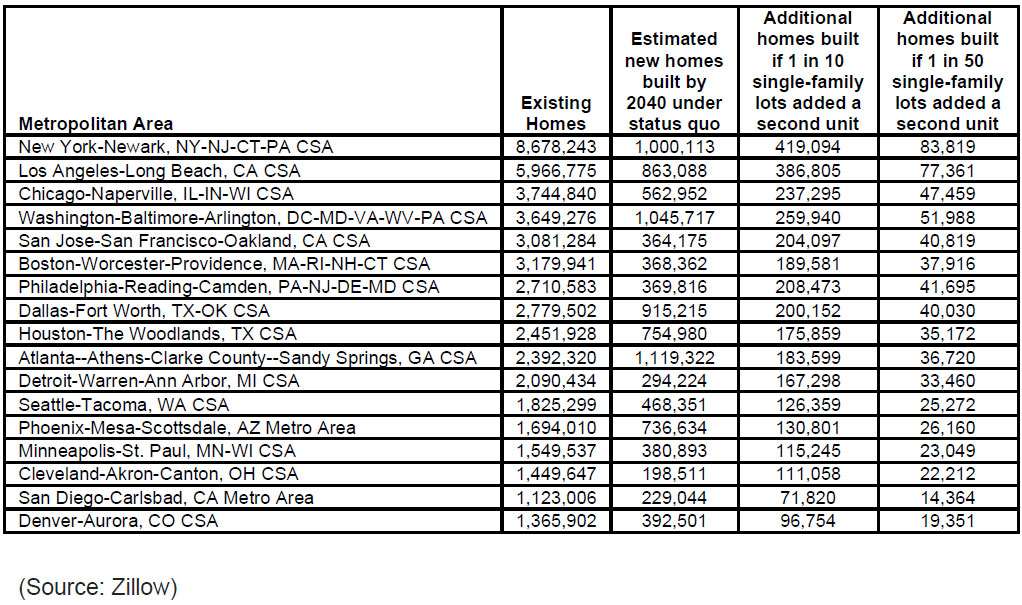

Building at the status quo over the next two decades is expected to produce about 10 million new homes across the 17 large metros analyzed nationwide, a more than 20% boost over the almost 50 million homes these markets currently have. Allowing for two units on just 10% of single-family lots would add an additional 3.3 million homes on top of that 10 million, a boost of almost 27% over current levels.

Single-family neighborhoods account for the lion's share of land in metropolitan America, and over the years have generally become insulated from denser redevelopment by a thickening tangle of regulations, reflecting entrenched local interests that benefit from keeping a neighborhood as it is. In America's expensive coastal cities especially, natural barriers and environmental concerns have exacerbated that trend, limiting most new housing to islands of density - often near transit or in formerly non-residential areas - in another wise stagnant sea of no-growth.

That shortage of new housing development coupled with sustained demand for it, especially in those pricey, coastal cities, has contributed mightily to an affordability squeeze. Over the past 20 years, the median home value in the Los Angeles metro area has more than doubled, in the San Francisco Bay Area it has nearly doubled, and in Seattle it has grown by almost two-thirds. In contrast, metros in the South where it has historically been much easier to build new homes, especially on the periphery, have seen home prices grow a little more than 10% in that time.

Looking inward at already-developed single-family tracts and allowing for two, three or even four homes where just one stands today could reignite housing development without contributing to sprawl, the analysis shows.

Indeed, Minneapolis and Oregon already have allowed for significantly more density in historically single-family neighborhoods, and other places like Los Angeles and Seattle have taken more modest steps to allow additional accessory dwelling units. This strategy also likely would expand the range of home types available, whereas the status quo produces mostly single-family homes and units in very large apartment buildings.

There are fears that intense densification may risk diminishing the character of neighborhoods - more concrete where there had been greenery, competition for street parking, etc. But in practice, allowing just 1 in 10 single-family homes in a given neighborhood to host a livable in-law suite above the garage, a bachelor apartment in the basement or a cottage in the back yard isn't likely to drastically alter an existing streetscape. Redeveloping more single-family lots and/or allowing them to host a triplex/quadplex or a row of four townhomes may result in more noticeable change, but also more significantly tackle the housing shortage and affordability crisis.

In the Los Angeles area, allowing four homes on 20% of single-family lots could yield a housing stock increase of more than 2.3 million homes, or a 53.4% boost over the current stock when combined with homes already expected to be built. This more extreme measure would add more than 1.5 million more homes than allowing only one additional home on the same lots.

"The challenge of solving big metros' housing affordability crisis is the scale of what's needed. If it was just a few more affordable apartment buildings it wouldn't be a problem, but we need a lot of additional supply to put the pace of long term price and rent growth in line with income and wage growth," said Skylar Olsen, Zillow's director of economic research. "Asking a few neighborhoods to absorb that change on their own is asking for a community to accept a totally different neighborhood in the future - a neighborhood different from the one they bought into and grew to love. So the questions become, if we could share the influx of new housing across the full metro, could we add enough and would anyone really notice?"

If the Los Angeles area, for example, continues to add housing largely as it has over the past two decades it could grow its housing stock by an estimated 14.5% over the next two decades. But if 1 in 10 single-family lots were redeveloped or otherwise allowed to accommodate a second home, the area's housing stock could grow by 21% over the same period - or nearly 387,000 additional homes.

Building at the status quo over the next two decades is expected to produce about 10 million new homes across the 17 large metros analyzed nationwide, a more than 20% boost over the almost 50 million homes these markets currently have. Allowing for two units on just 10% of single-family lots would add an additional 3.3 million homes on top of that 10 million, a boost of almost 27% over current levels.

Single-family neighborhoods account for the lion's share of land in metropolitan America, and over the years have generally become insulated from denser redevelopment by a thickening tangle of regulations, reflecting entrenched local interests that benefit from keeping a neighborhood as it is. In America's expensive coastal cities especially, natural barriers and environmental concerns have exacerbated that trend, limiting most new housing to islands of density - often near transit or in formerly non-residential areas - in another wise stagnant sea of no-growth.

That shortage of new housing development coupled with sustained demand for it, especially in those pricey, coastal cities, has contributed mightily to an affordability squeeze. Over the past 20 years, the median home value in the Los Angeles metro area has more than doubled, in the San Francisco Bay Area it has nearly doubled, and in Seattle it has grown by almost two-thirds. In contrast, metros in the South where it has historically been much easier to build new homes, especially on the periphery, have seen home prices grow a little more than 10% in that time.

Looking inward at already-developed single-family tracts and allowing for two, three or even four homes where just one stands today could reignite housing development without contributing to sprawl, the analysis shows.

Indeed, Minneapolis and Oregon already have allowed for significantly more density in historically single-family neighborhoods, and other places like Los Angeles and Seattle have taken more modest steps to allow additional accessory dwelling units. This strategy also likely would expand the range of home types available, whereas the status quo produces mostly single-family homes and units in very large apartment buildings.

There are fears that intense densification may risk diminishing the character of neighborhoods - more concrete where there had been greenery, competition for street parking, etc. But in practice, allowing just 1 in 10 single-family homes in a given neighborhood to host a livable in-law suite above the garage, a bachelor apartment in the basement or a cottage in the back yard isn't likely to drastically alter an existing streetscape. Redeveloping more single-family lots and/or allowing them to host a triplex/quadplex or a row of four townhomes may result in more noticeable change, but also more significantly tackle the housing shortage and affordability crisis.

In the Los Angeles area, allowing four homes on 20% of single-family lots could yield a housing stock increase of more than 2.3 million homes, or a 53.4% boost over the current stock when combined with homes already expected to be built. This more extreme measure would add more than 1.5 million more homes than allowing only one additional home on the same lots.

"The challenge of solving big metros' housing affordability crisis is the scale of what's needed. If it was just a few more affordable apartment buildings it wouldn't be a problem, but we need a lot of additional supply to put the pace of long term price and rent growth in line with income and wage growth," said Skylar Olsen, Zillow's director of economic research. "Asking a few neighborhoods to absorb that change on their own is asking for a community to accept a totally different neighborhood in the future - a neighborhood different from the one they bought into and grew to love. So the questions become, if we could share the influx of new housing across the full metro, could we add enough and would anyone really notice?"

Sign Up Free | The WPJ Weekly Newsletter

Relevant real estate news.

Actionable market intelligence.

Right to your inbox every week.

Real Estate Listings Showcase

Related News Stories

Residential Real Estate Headlines

- More Americans Opting for Renting Over Homeownership in 2024

- BLOCKTITLE Global Property Tokenization Platform Announced

- Small Investors Quietly Reshaping the U.S. Housing Market in Late 2024

- Greater Miami Overall Residential Sales Dip 9 Percent in November

- U.S. Home Sales Enjoy Largest Annual Increase in 3 Years Post Presidential Election

- U.S. Housing Industry Reacts to the Federal Reserve's Late 2024 Rate Cut

- U.S. Home Builders Express Optimism for 2025

- Older Americans More Likely to Buy Disaster-Prone Homes

- NAR's 10 Top U.S. Housing Markets for 2025 Revealed

- U.S. Mortgage Delinquencies Continue to Rise in September

- U.S. Mortgage Rates Tick Down in Early December

- Post Trump Election, U.S. Homebuyer Sentiment Hits 3-Year High in November

- Global Listings Aims to Become the Future 'Amazon of Real Estate' Shopping Platform

- Greater Las Vegas Home Sales Jump 15 Percent in November

- Ultra Luxury Home Sales Globally Experience Slowdown in Q3

- World Property Exchange Announces Development Plan

- Hong Kong Housing Market to Reach Equilibrium in Late 2025

- Construction Job Openings in U.S. Down 40 Percent Annually in October

- U.S. Mortgage Applications Increase in Late October

- World Property Markets, World Property Media to Commence Industry Joint-Venture Funding Rounds in 2025

- New Home Sales Hit 2 Year Low in America

- U.S. Pending Home Sales Increase for Third Consecutive Month in October

- Pandemic-led Residential Rent Boom is Now Fizzling in the U.S.

- Emerging Global Real Estate Streamer WPC TV Expands Video Programming Lineup

- 1 in 5 Renters in America Entire Paycheck Used to Pay Monthly Rent in 2024

- U.S. Home Sales Jump 3.4 Percent in October

- Home Buyers Negotiation Power Grows Amid Cooling U.S. Market

- Canadian Home Sales Surge in October, Reaching a Two-Year High

- Greater Orlando Area Home Sales Continue to Slide in October

- U.S. Mortgage Credit Availability Increased in October

- U.S. Mortgage Rates Remain Stubbornly High Post Election, Rate Cuts

- Construction Input Prices Continue to Rise in October

- BETTER MLS: A New Agent and Broker Owned National Listings Platform Announced

- Home Prices Rise in 87 Percent of U.S. Metros in Q3

- Caribbean Islands Enjoying a New Era of Luxury Property Developments

- The World's First 'Global Listings Service' Announced

- Agent Commission Rates Continue to Slip Post NAR Settlement

- Market Share of First Time Home Buyers Hit Historic Low in U.S.

- Greater Palm Beach Area Residential Sales Drop 20 Percent Annually in September

- Mortgage Applications in U.S. Dip in Late October

Reader Poll

Marketplace Links

This website uses cookies to improve user experience. By using our website you consent in accordance with our Cookie Policy. Read More